Resilient Futures looks at companies, organizations, innovations, business models, methodologies, financial models, and policies that bring creativity and imagination to the development and deployment of solutions that can restore ecological balance and build equitable prosperity.

Resilience is about bouncing forward. It is simply too late to “build back better,” a well-meaning phrase often paired with “thoughts and prayers” in the aftermath of catastrophes. There is no going back. There is nothing to go back to. Tipping points for climate, biodiversity and health are colliding.

Resilience means “building for better.”

Integrative design, a methodology that takes its cue from nature, provides a framework for how to do just that. There are three core principles:

Start with outcomes: What are the desired results? Also, consider possible unintended consequences.

Draw from an expanding, cross-pollinating assemblage of practices, technologies and business models. Integrative design is dynamic and transformative. It provides a roadmap for iterative improvement.

Evaluate each part of a system to make sure it performs at least two meaningful functions. The more functions, the better.

This is a whole systems approach that can be used to improve everything from the energy efficiency of buildings to the design of products, services and processes.

My Background

In a world of specialists, I am a silo-skipping generalist.

As a journalist, I have covered business, marketing, science, transportation, engineering and tech stories, picking up some wonderful teachers along the way. I have interviewed energy experts, wildlife biologists, virologists, and brand strategists, designers, business consultants, engineers, educators, computer scientists, architects, urban planners, politicians, farmers, designers and veterinarians. Despite my parents’ best intentions, I talk to strangers.

I love a good trade show and am a regular reader of a staggering range of industry publications. I treasure my networks of specialist “brain trusts,” who are always there to turn to for guidance. From them I have learned to ask better questions and also to more quickly spot patterns and synergies across disciplines.

I have also worked on the both sides of the byline:

writing for newspapers and magazines (including one the first major articles on zoonotic disease threats for BusinessWeek)

traveling for television documentaries (chasing horses, bears, coyotes, wolves, birds, pathogens and biologists)

embedding as part of the core team for a large military / civilian humanitarian exercise (Operation: Strong Angel)

heading up a Business Intelligence practice (better described as applied journalism) for a leading brand design consultancy (COLLINS).

For COLLINS, I wrote dozens of business backgrounders and also several white papers on issues with relevance to clients—and also clients soon to be. It was fascinating to work closely with strategists, designers, legacy companies and game-changing startups, to see how idea packaged and messages crafted.

I learned that when branding is done well, the most significant work isn’t what the consumer sees. It isn’t clever logos, elegant typography, bold visuals or snappy copy. Those are important. They win awards.

But the big payoff is internal, an articulation of a company’s purpose that can be transformational. For example, when a company that uses environmentally friendly green chemistry to make pulp from recycled paper (a material that will then be used to make new cardboard and paper products) understands itself not as a recycled paper company, but instead as part of a greater “Clean Materials Economy,” it opens up “the adjacent possible. The company can see how its work dovetails with that of other businesses. New use cases and partnerships are possible. New customers, too.

“The adjacent possible” a phrase coined by biologist and complexity theorist Stuart Kauffman, to describe the collisions of Earth’s “starter” molecules. Over time, these collisions led to the creation of all the molecules required for the emergence of life.

In his book, Where Good Ideas Come From, author Steven Johnson describes the adjacent possible using the metaphor of doors:

“Think of it as a house that magically expands with each door you open. You begin in a room with four doors, each leading to a new room that you haven’t visited yet. Those four rooms are the adjacent possible. But once you open one of those doors and stroll into that room, three new doors appear, each leading to a brand-new room that you couldn’t have reached from your original starting point. Keep opening new doors and eventually you’ll have built a palace.”

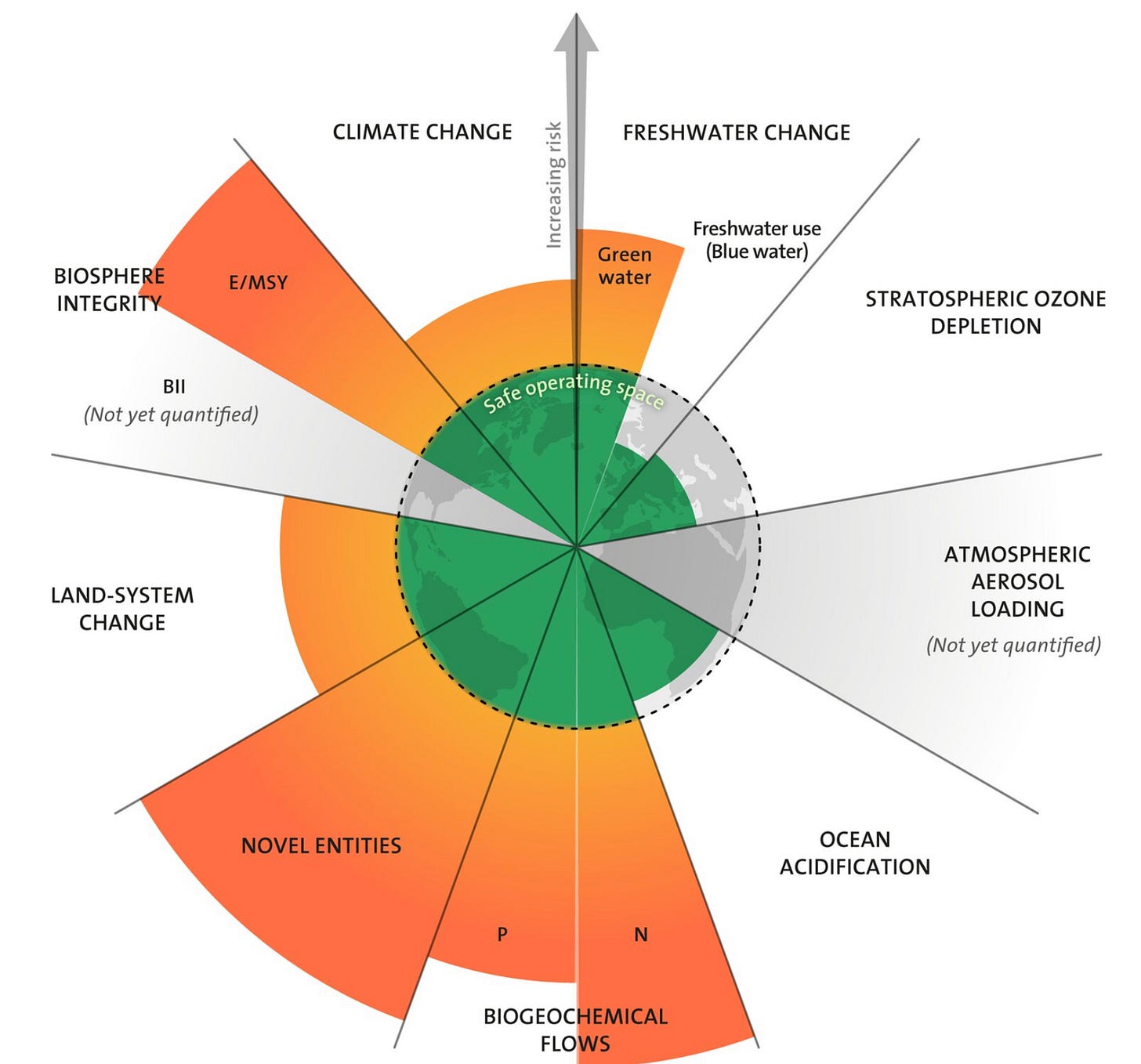

Resilient Futures grew out this eclectic mix of experience and perspective, and also a profound sense of urgency. Climate change is real. Wildlife extinctions are real. The staggering loss of fertile topsoil from the world agricultural lands is real. Six of the nine “planetary boundaries” that scientists have told us are must-haves for humans to live happily on Earth have been breached.

We now live in a world where heat-stroke insurance is a thing because heat waves have become much more intense and last longer. We are starting to drop like flies. Meanwhile, flies and other insects, are dropping off the radar altogether.

The good news is that no new save-the-planet technologies are needed to keep us from flying off a climate cliff into a hot, soggy, poisoned planet future. Resilience is about using what’s on hand more effectively: seeing old ideas with fresh eyes and experimenting with combinations of technologies, methodologies and business models.

Of course, the more good ideas the better.

Across every sector, companies that lean into the constraints of climate change are finding new and better ways to do business, often offering a competitive advantage. For example, a developer of “net zero” buildings in Boulder, Colorado is able to get a 20 basis point discount on loans because the mortgages on his high performance buildings are easier for the bank to sell. This cheaper cost of capital effectively zeros out the additional costs of building cleaner and greener. That’s an instant return on investment (ROI), where energy savings start to accrue on day one.

There are eureka moments in labs where better batteries, non-toxic fabric dyes, and compostable packaging materials are being developed. It’s boom times for the clean molecules business, with AI speeding up the discovery of new enzymes and catalysts to make products (e.g., detergents) using fewer ingredients, less water and less energy.

Roughly a third of oil goes toward making plastics and petrochemicals, including fertilizers and pesticides. The accelerating adoption of regenerative agriculture, which focuses on restoring and improving soil microbiomes, reduces the need for chemical inputs. It builds up biodiversity below and above ground, both critical for keeping carbon out of the upper atmosphere.

Now it is a race against time. Will these efforts—clean energy / efficiency, nature-based solutions, and materials efficiency—be enough? Without them the answer is clear and dire. When everything is at stake, there is also nothing to lose. On the bright side, we probably cannot do worse. So why not do better?

Several years ago, driving across Arizona to film the release of a pair of Mexican Gray wolves in the Blue Mountains, a senior scientist from the National Wildlife Foundation traveling with the crew quoted from Aldo Leopold’s essay, Thinking Like a Mountain.

The essay, from a A Sand County Almanac, recounts the day Leopold, then early in his career with Forestry Service, shot and killed a mother wolf.

“…In those days we never heard of passing up a chance to kill a wolf. In a second we were pumping lead into the pack, but with more excitement than accuracy: how to aim a steep downhill shot is always confusing. When our rifles were empty, the old wolf was down, and a pup was dragging a leg into impassable slide-rocks.

We reached the old wolf in time to watch a fierce green fire dying in her eyes. I realized then, and have known ever since, that there was something new to me in those eyes—something known only to her and the mountain. I was young then and full of trigger-itch; I thought that because fewer wolves meant more deer, that no deer would mean a hunters’ paradise…

…I now suspect that just as a deer herd lives in mortal fear of its wolves, so does a mountain live in mortal fear of its deer. And perhaps with better cause, for while a buck pulled down by wolves can be replaced every two or three years, a range pulled down by too many deer mail of replacement in as many decades…”

Thinking Like a Mountain is about humility, understanding that we don’t know what we don’t know, until we do. Once we do, we have to change.

It means looking more deeply and broadly. Leopold spent the rest of his career as a pioneering conservationist, studying how the parts create the whole. From micro to macro, it is all of a piece.

Leopold understood that health of the Earth depends on the health of the earth. Or has he put it, “the health of the land.”

That epiphany is the beating heart of Resilient Futures.