Why the Government Whole is (or was) Worth So Much More than the Sum of its Parts

on sniffer dogs, seeds & intelligence; systems, networks & consequences; the difference between business & government; wood chippers, chainsaws and intentional ignorance

Where do you start when you could begin anywhere?

How about sniffer dogs? They work for the joy of a job well done and treats from their trainers, using their legendary canine sense of smell to root out contraband and pathogens. Tasked with keeping millions of people (also crops and livestock) safer and healthier, they work better, faster and cheaper than any human-designed technology. Yet the dogs have now been sidelined by the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE). Budgets for dog food and kenneling have been zero’ed out. There is no more money for training. Or trainers. A proven first-line defense against disease outbreaks, one that comes with tail wags thrown in for free, is no more.

Or we could start with seeds since it is Spring and planting season is just getting underway.

The US Department of Agriculture’s National Plant Germplasm System (USDA-NPGS), a vast collection of seeds and plants, serves as a critical insurance policy for the nation’s $1.5 trillion food system. That’s $1.5 trillion annually, which is roughly three times the value of all the gold in Fort Knox. The vast wealth stored in NPGS seed banks represents decades of meticulous work: 600,000 genetic lines developed from more than 200 food crops and fruit trees. Our food future depends on being able to breed plants that can survive a constantly changing array of threats: insect pests, diseases, floods, droughts, heatwaves. All threats made worse by climate change.

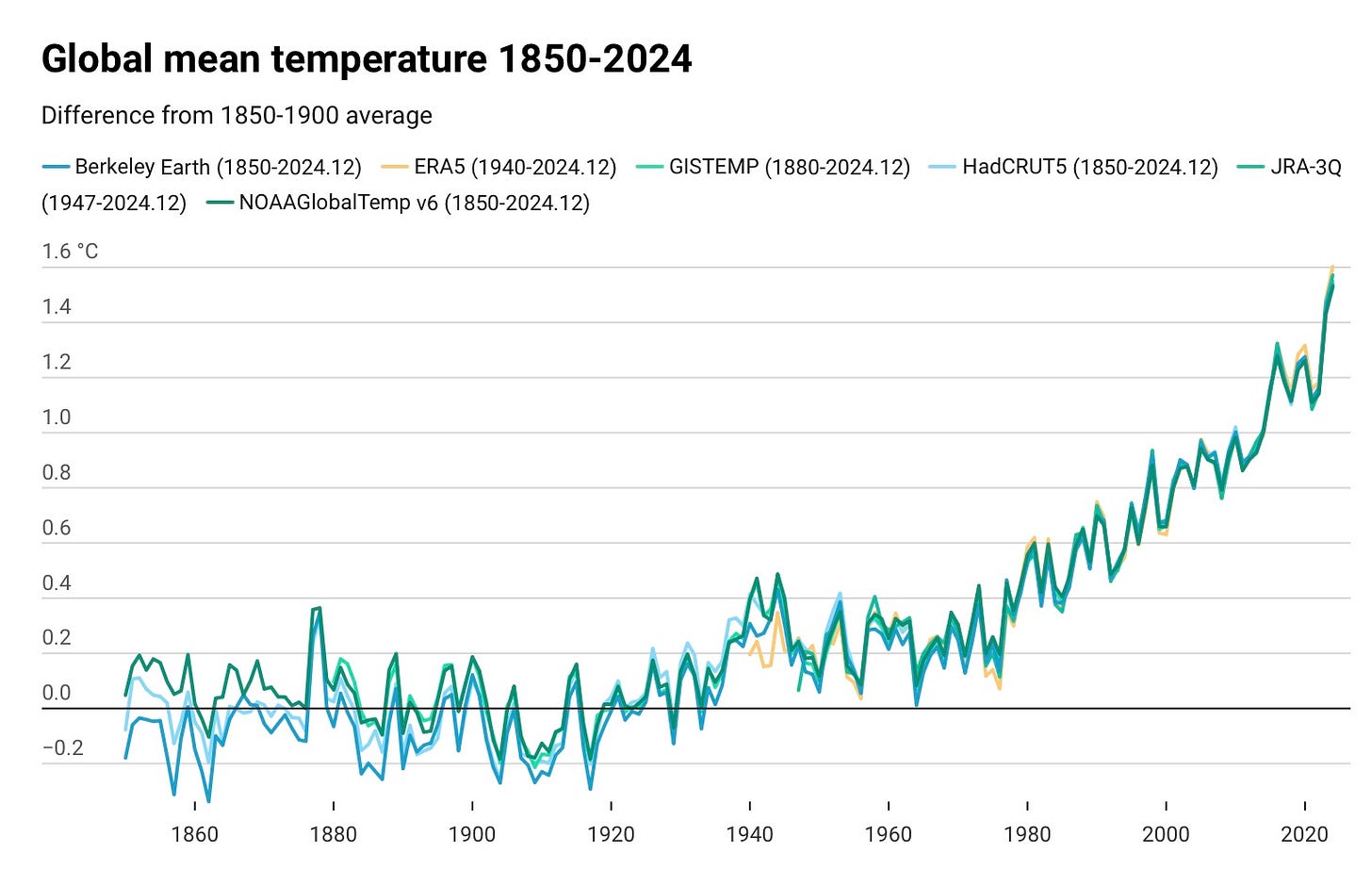

The past ten years have been the hottest in 175 years of World Meteorological Organization record-keeping, a trend that shows no signs of slowing down. When it gets too hot, plants stop growing, crops fail, farmers lose money, food prices spike and people go hungry.

Costing only 0.000008% of the federal budget, NPGS, an irreplaceable national treasure, is a bargain. Yet DOGE, laser-focused on reducing head counts and slashing budgets, laid off several of the 300 scientists spread across a national network of 22 field stations. A few were rehired, but the loss of any staff in such a small operation is a significant loss of expertise; also, fewer hands on deck to do the job. NPGS is a living collection, which means a selection of seeds must be planted in the field each year to keep the collection viable and also to test out new varieties. Timing matters. Miss the Spring planting season and that’s it for the year.

Or we could start big, which is what DOGE did in January when it put USAID and its 10,000 employees through “the wood chipper.”

In a blink, a vast logistics network distributing urgently needed food, water and medical aid to hundreds of millions of people in 130 countries—a global network that took decades to build—went dark. Supply chains were frozen. Food already paid for was abandoned in warehouses. Funding was cut off for PEPFAR, a program with broad bipartisan support that provided life-saving drugs to people with AIDS; effectively, a genocide by Executive Order.

In response to a catastrophic earthquake in Myanmar in March, USAID sent three advisors instead of a team of trained first responders. Hundreds of first responders, experts in disaster response, had just been laid off. Then the three advisors were laid off, too.

American farmers lost $2 billion in annual sales. Long-standing contracts were canceled with dozens of organizations that handled the “last mile” delivery of aid directly into communities. American diplomats lost “soft power”: the eyes, ears and geopolitically critical good will of a frontline network of appreciative allies able to provide real time, on-the-ground insights and connections.

Gutting USAID also trashed the best, cheapest, most effective early disease detection and prevention network the US—and the world—has ever known. Although only a few dozen USAID staffers focused specifically on disease outbreaks, they supported a remarkable network of thousands of trained community health works across Africa, Asia and Latin America who served as invaluable sentinels in the field. Almost all the USAID staffers were laid off and funding for community health workers was cut. Without staff to properly dispose of pathogens in field labs, concerns have been raised about the potential for bioterrorism.

The loss of USAID, along with US withdrawal from the World Health Organization (WHO), makes everyone everywhere, including Americans living in the United States, more vulnerable to disease.

The DOGE savings? An estimated 0.3% of the federal budget.

COLLECTIVE, AMPLIFYING IMPACT

These three programs—sniffer dogs, seed banks and USAID—delivered tremendous value, preventing and containing disease outbreaks that threatened people, livestock and crops. The cost of a single major outbreak missed because these programs were cut would quickly dwarf any line item savings.

Collectively, these programs—along with dozens more throughout the federal government that have been weakened or eliminated over the last several months—provided dovetailing layers of protection: systemic resilience. For example, if sniffer dogs missed a plant pathogen, then scientists at NPGS could begin breeding resistant crops. USAID staffers armed with an early warning about a disease outbreak from a community health worker could draw on the expertise of CDC epidemiologists to develop plans for containment. At the same time, CDC could issue travel warnings and alert the medical community in the US to be on the lookout for cases. For diseases that might also be spread by animals, USDA and USGS would be looped in as well.

Resilience has been replaced with vulnerability. The whole was worth so much more than the sum of its valuable parts and what remains of the “parts” has been badly damaged.

A partial list of what has been lost:

Medical

Research on vaccine and anti-viral drug development, reproductive health, gun violence prevention and food safety scaled back or eliminated at the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH), which are all part of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS)

Access to medical services at the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) became more difficult due to budget cuts, layoffs and policy changes. Programs at Medicaid (HHS) Medicare (HHS) and the Social Security Administration (SSA) are in the DOGE cross-hairs.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) capped the amount of grant money that could be spent on offices and lab space to 15%, putting scientists in the awkward position of having funds to do research, but not enough to cover the costs of running a lab. A judicial order put a temporary pause on the new policy.

HHS canceled more than $12 billion in grants to state health departments to track infectious diseases and provide mental health services, addiction treatment and address other urgent health issues. A coalition of 23 Democratic states the District of Columbia sued, winning a temporary injunction against the cuts.

Staff cuts at the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (HHS-AHRQ), knee-capped its ability to evaluate the effectiveness of medical procedures.

Research data sets on the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) website were modified and purged.

Punitive freezes on government research grants to universities have halted work on tuberculosis, ALS and the long-term safety of radiation therapy for treating cancer, among many other studies. Lab staff has been let go and a lab animals euthanized. Years of research is at risk of being squandered.

Food & Ag

A USDA program providing funds to schools and food banks to buy fresh produce from local growers was cut: a lose-lose-lose for nutrition, small farmers and keeping money circulating within communities.

A half billion dollar USDA program supporting local food banks was also cut, at a time when food banks are struggling to meet increasing need.

Staff cuts at the Agricultural Research Service (ARS), the USDA’s principal in-house research agency, included layoffs of honeybee experts in the midst of the worst commercial bee die-off in US history. According to USDA, pollinators—mostly bees—“add more than $18 billion in revenue to crop production every year.”

Hundreds of journal subscriptions were cancelled due to budget cuts at the National Agricultural Library (USDA). The loss has been compared to “…burning down the Library of Alexandria. You can’t call it the National Agricultural Library if you don’t subscribe to the main ag journals.”

A dozen staffers were let go from the newly built National Bio and Agro-Defense facility, a collaborative effort by USDA and Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to study dangerous foreign, emerging and zoonotic diseases. According to reports, at least 28 were initially fired, but several people were then quickly rehired.

The US Forest Service (USDA) cut a $75 million grant to plant shade trees in poor neighborhoods—areas that tend to suffer the most during heatwaves—over concerns the program didn’t align with the government’s position on Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI).

Nature & Environment

Staff cuts and office closures at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which is part of the Department of Commerce (DOC - NOAA) impacted efforts to track climate change and predict weather. Extreme heat and an increase in insect-borne diseases are among the health-related impacts of climate change.

Staff cuts at the US Geological Survey (USGS), which oversees several wildlife health programs, means fewer scientists in the field to notice sick animals that may be carrying zoonotic diseases (diseases that affect both animals and people, including COVID and bird flu); track invasive species; collaborate with other government labs studying pathogens carried by ticks and mosquitoes.

A government-wide strategy to freeze or repeal regulations across more than 400 federal agencies, including many designed to protect health and safety.

•••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••

Losing resilience and increasing vulnerability does not mean we are in for another global pandemic, although bird flu could easily be a contender. Rather, it is the near-certainty of a non-stop epidemic of epidemics affecting people, livestock, poultry, crops, wildlife and wilderness.

It is the near-certainty of a blighted future.

SYSTEMS THINKING

The DOGE approach of cost-cutting is blind to systemic benefit, a core strength of a well-run government. Instead, DOGE conflates efficiency with line item savings, setting targets for layoffs, the number of leases broken, and wood-chippering of entire agencies. By the time the dust clears, the US government will be smaller, but it will also be. considerably lesser.

According to economist Milton Friedman, the goal of business is to maximize profits for shareholders. But the goal of government is different. It is, or should be, to maximize prosperity for its citizens. To quote Abraham Lincoln, “…government of the people, by the people and for the people.”

Business sells. Government provides.

Specifically, government provides the social, economic, political, knowledge, legal and physical infrastructures that enable citizens, and also businesses, to prosper.

To run a government as if it were a business is to miss the point.

But it raises the question: If success in business is measured in profits, then how might success in government be measured?

Integrative design is a three-step framework developed by Amory Lovins, cofounder of energy consultancy RMI, to calculate and analyze systemic benefits.

First, start with a list of desired outcomes, including outcomes to avoid.

Next, use a constantly expanding array of technologies, business and financial models to achieve those outcomes. Good can always get better.

Finally, make sure every part of the system delivers at least two benefits. The more, the better.

The desired outcome is the metric to assess value.

As a test, let’s say the desired outcome is “healthy citizens.” How do sniffer dogs stack up?

They detect pathogens, which helps keep people, livestock and crops healthy. (Step 1)

They prevent illness, which would be an undesired outcome. (Step 1)

There are also collateral “goods.” Healthy people don’t need to take sick days off from work or school. They are better able to support their families, pay bills, pay taxes and do well academically. (Step 3)

Likewise, healthy livestock and crops means less expense and more profit for farmers, and more stable food supply. (Step 3)

Step 2 is about leveraging value. The data collected by sniffer dogs and their handlers in the field can be shared with scientists and researchers at USDA, USAID, CDC, FDA, NIH, NSF, USGS, DHS snd EPA. This data, along with data provided by the other agencies, can be used to collaborate on projects and develop strategies to strengthen public health policy. This builds resilience.

The Integrative Design framework can also be used to identify areas of overlap between agencies and departments, suggesting the potential for combining and streamlining services. It can be used to identify new ways to use existing resources to better serve citizens.

This is the difference between the false savings of chainsaw-style cuts and, as my mother would say, “a real bargain.”

Unfortunately, it is nearly impossible to reconstruct a system with such rich complexity once it has been so carelessly, thoughtlessly hacked to pieces. The “real bargain” of a multi-layered, resilient health system has been squandered.

INTENTIONAL IGNORANCE

“The best science available” is a phrase I first heard at a government press briefing about BSE, a brain-wasting disease more commonly known as Mad Cow.

On that particular topic, the best science possible was coming from the UK where the disease had first been identified. Yet the spokesman at the briefing was unwilling to cede any territory, assuring reporters repeatedly that USDA’s science was the best science available and therefore the best science period.

It was an impressively artful spin. And now that America’s research bench has been hollowed out, one we are likely to hear often in the coming years.

••••••••••••••••••••

In took only a few weeks to scrub government websites and data sets of anything that could be interpreted as Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI).

Climate change has also been disappeared from the conversation. Last year, those two words could elevate an NSF grant proposal for review. Now they are on a list of verboten vocabulary almost sure to get a grant application tossed.

Information about climate change has been banished from government websites. Funding for the National Climate Assessment, a prestigious, congressionally-mandated quadrennial report tasked with helping the nation prepare for what’s in store, has been cut. The first Assessment was published in 2000 and the most recent—and possibly the last—in 2023. The US has also pulled out of the Paris Agreement, a UN treaty calling for reductions in greenhouse gas emissions.

In the Age of AI, it is easy to pre-write the future. Just edit the past and censor the present.

Large Language Models (LLMs) are being trained on information that has been deliberately manipulated, riddled with gaps. Unreliable information is coming from what ought to be a credible source: the government. As we rely more and more on AI as an information gatekeeper, it will become harder to know what has been left out; harder to know what we don’t know or what we used to know.

Federal funding for libraries and museums (less than 0.01% of the budget) is also in the cross-hairs. Army and Navy libraries have already been ordered to purge their collections of anything smacking of DEI. Maya Angelo books have been kicked out of the Naval Library, but there are still two copies of Hitler’s Mein Kampf on the shelf.

Soon, we could be left not with the best science, the best history, the best knowledge possible, but instead with the dregs of whatever’s available and, of course, approved.

••••••••••••••••••••

Knowledge is power. Ignorance is weakness. Intentional ignorance inflicted by those in power—those with a knowledge advantage—is a weapon.

Knowledge is our best, and only, defense. We must fight for what we have taken for granted: the rule of law, governmental checks and balances, a nation that values education, invests in scientific research, cares about the environment, supports libraries, museums and a free press, offers opportunity, provides humanitarian support, embraces diversity, celebrates creativity, treasures its immigrant history, welcomes foreign students and offers new immigrants paths to citizenship.

If that isn’t enough, then fight for the sniffer dogs. They devoted their lives for our well-being, with tail wags thrown in for free.

••••••••••••••••••••

Nearly four hundred years ago, in April 1663, Galileo was put on trial, accused by the Roman Catholic Church of heresy. The astronomer had written that Earth revolved around the Sun. He was right. He lost.

“We pronounce, judge, and declare, that you, the said Galileo… have rendered yourself vehemently suspected by this Holy Office of heresy, that is, of having believed and held the doctrine (which is false and contrary to the Holy and Divine Scriptures) that the sun is the center of the world, and that it does not move from east to west, and that the earth does move, and is not the center of the world.”

As part of his sentence, Galileo was required to recite the Seven Penitential Psalms once of week for three years. For each of those three years, Earth continued to circle the Sun just as Galileo said it would; just it had for the previous 4.3 billion years; just as it will for the next 5 billion years, until our friendly neighborhood star expands into a “red giant,” incinerating Earth in the process.

It took the Church three centuries to reverse its ruling, which didn’t do Galileo much good, but was a notable win for truth.

We haven’t got 300 years. But Galileo was alone, an army of one fighting against a Church with the authority to write the rules. We are many. We are not alone. We know the laws that are being broken, ignored, mangled and rewritten, including those of physics, biology and chemistry. We know what better looks like. We know what has already been lost.

So where do you start when you could begin anywhere? Start wherever you can.