This is the second of three posts on different ways to get to better answers faster.

Part 1: Integrative Design, a methodology, and Negawatts, a framework for assessing benefits across value chains

Part 2: The metaphors of Peripheral Vision and the Theory of the Adjacent Possible for assessing and leveraging insights

Part 3: The 7 Characteristics, a heuristic, and the Circular Dividend, the transformational impact of doing different

Peripheral Vision

It is a fact—and also a good metaphor—that without peripheral vision, you would trip over your own feet. Splat. Try to get up and you will trip, again. There is no going forward, only down.

Most of what we see—90% of our visual field—is information acquired on autopilot, real-time situational awareness that keeps us upright and safe. Yet we operate as if the remaining 10% of our visual field, the part literally in front of our noses, is all there is to see.

This sliver of a considerably bigger picture dominates the language of education, business and politics. We are told to keep our eyes on the prize, noses to grindstones, to stay on course, ignore distractions and never ever lose focus. Yet for those bold enough to tear off the blinders and bring peripheral vision back into the mix, there is a considerable advantage.

Peripheral vision, in fact and metaphor, is about awareness. It operates at the fuzzy edges where nothing is clear and anything is possible. Imagination, which goes hand in hand with peripheral vision, is how sense is made from nonsense. Is that a shadow or lion? Is it a bird? A plane? Superman?

Imagination is nature’s digital twin, a low stakes safe space to try out different futures. What happens if you paint outside the lines, ignore the rules, make up new rules, rearrange puzzle pieces, or stray off the beaten path?

As children, we have excellent peripheral vision because everything is new and in urgent need of a plausible explanation. This is the “beginner’s mind” so valued in zen meditation. Children are open to possibilities, at ease with the ridiculous. They are playful, constantly testing the limits of logic. The absurd isn’t a wrong answer. It’s a “think different” answer.

Getting the joke, and the delicious endorphin hit that comes with laughter, requires recognizing the difference between what’s plausible, what’s not, and understanding the difference.

As we grow up and learn more about the world, the need for fanciful explanations diminishes. Our field of view gradually narrows to that 10% in front of our noses and imagination starts to take a back seat to the serious, adult “i’s”: invention, innovation, iteration, inspiration, insight. Yet those who are the most inventive, innovative and insightful are also the ones with the best peripheral vision and the imagination that goes hand in hand.

Visionaries don’t look off into the distance to see the future. They glance sideways to catch a preview.

The metaphor puts the emphasis on sight, but it is about paying attention, constantly taking in new information and testing it against what we think we know. It is a skill that improves with practice:

Do something familiar. Take a walk around the block or around the office. What do you notice in your everyday world that you never noticed before? What does it remind you of? How does it change your understanding of things? Trying making up a story weaving in the new details.

Do something different. Take a class. Go to an event where you don’t know anyone and make new friends. Try cooking a new dish. Listen to different styles of music. Read. Read some more. Make art. Travel. Peripheral vision automatically kicks in to help you navigate through unfamiliar terrain.

Always look for patterns, which can take all kinds of forms. There are patterns in design, materials, music, strategies, business models—just about anything you can think of. Spotting patterns is key to identifying trends, imagining new applications and having the flashes of insight that can change everything. A press can be used to squish grapes to make wine, or squish ink-covered letterforms onto paper to make a book.

The Adjacent Possible

“Make your future so irresistible, it becomes inevitable.”

That is the tagline/mission statement at COLLINS, a branding and business consultancy where I worked with new business and strategy teams. An “irresistible future” is aspirational, inspirational and crackling with purpose. It brings clarity to an organization’s mission, both internally and among stakeholders. It taps into an enterprise-level peripheral vision, imagining a company’s future capabilities and customers.

An irresistible future, at least initially, isn’t always obvious, though in hindsight always seems inevitable. How did Apple go from selling desktop computers to the App Store? Or Amazon expand from online retail to cloud computing? How did Nike, from its unlikely beginnings as a niche sneaker company known for using a waffle iron to make soles for running shoes end up outfitting Team USA at the Paris Olympics?

Each took a path through the adjacent possible.

I first came across that lovely phrase in Steve Johnson’s fascinating book, Where Good Ideas Come From: The Natural History of Innovation.

“…The adjacent possible is kind of shadow future, hovering on the edges of the present state of things, a map of all the ways the present can reinvent itself…

…The strange and beautiful truth about the adjacent possible is that its boundaries grow as you explore those boundaries. Each new combination ushers new combinations into the adjacent possible. Think of it as a house that magically expands with each door you open. You begin in a room with four doors, each leading to a new room you haven’t visited yet. Those four rooms are the adjacent possible. But once you open one of those doors and stroll into that room, three new doors appear, each leading to a brand new room that you couldn’t have reached from your original starting point. Keep opening new doors and eventually you’ll have built a palace…

My job at COLLINS was to explore the adjacent possible of companies, to open doors and dash through rooms to see how their missions might evolve and grow. Peripheral vision is expansive, non-linear and unafraid to takes leaps of logic, while the adjacent possible demands discipline. There is an order to how things can happen. Today sets the stage for tomorrow. Used in tandem, peripheral vision and the adjacent possible can provide powerful strategic insights. How might a company’s products or services be used in other sectors? Who is doing similar work in different fields that might make an interesting partner? What will the circle of stakeholders look like in two, five, even ten years? What kinds of products and services will the world need and want in two, five and ten years?

••••••••••

But there is more than poetic framing and spotting business opportunities to the adjacent possible. There is math.

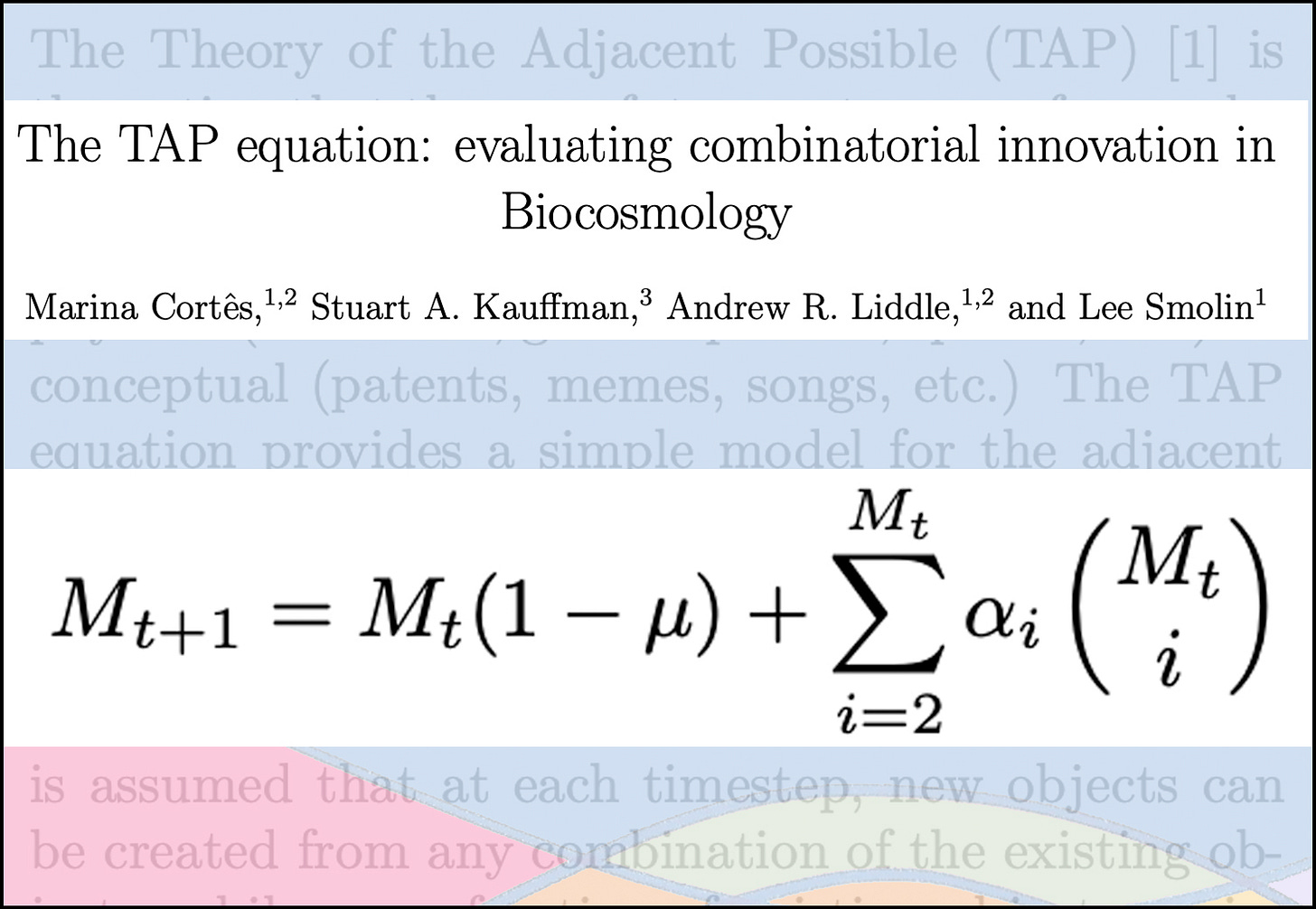

Johnson was referencing the Theory of the Adjacent Possible (TAP), a mathematical equation developed by Stuart Kauffman, a theoretical biologist and one of the original researchers at the Santa Fe Institute.

The origins of TAP begin with the origins of life on Earth. The planet’s bare-bones molecular starter kit, which included carbon, hydrogen and methane, wasn’t sufficient to create even the most basic living organism. It took eons, but eventually there were enough collisions between the original molecules, combining and making new molecules in the process, to create the components of life. Those were “first order” adjacent possibles. Then those components combined, opening the door for the first life forms to emerge. (See The TAP equation: evaluating combinatorial innovation in Biocosmology, co-authored with cosmologists Marina Cortês and Andrew Liddle and theoretical physicist Lee Smolin)

“What is actual now enables the next possible: the adjacent possible,” explains Kauffman.

For more than three billion years the only life forms on Earth were single-celled organisms. Then, a little more than half a billion years ago during the Cambrian Explosion, a comparative blink lasting less than 25 million years, the adjacent possible hit another critical mass. To use Kauffman’s analogy, there were enough tools in the toolbox, enough spare parts, to make all kinds of new things. All the major groups (phyla) of animals and plants that exist today emerged in flurry of evolutionary innovation.

The pattern of a long period of slow progress, followed by seemingly instant burst in creativity, variety and quantity is the TAP signature. On a graph, a virtually horizontal line suddenly takes a 90° turn vertical.

The TAP can also be applied to the development of human technology. Each innovation, each new literal tool, creates new possibilities in two ways. First, through combinations. Combine movable type with wine press and you’ve got a printing press, itself an adjacent possible for the emergence of mass communication.

At the same time, each new tool also has the potential to be used in a variety of ways. Kauffman cites the example of a screw driver, which can be used to screw in a screw, smear putty on a wall, as a baton to conduct an orchestra, or a weapon to defend against an attacker. “Anything can be used for more than one thing,” he notes.

When there are only a few tools, it takes a while for a next tool to emerge. This is the long, horizontal part of the graph. It took three million years from the time of our hominid ancestor Australopithecus to the early modern humans of 40,000 years ago to develop a few dozen stone tools.

The Agricultural, Industrial and Digital Revolutions were the equivalent of Cambrian Explosions, each leading to a burst of technological creativity. Today, there are billions of tools, with more invented all the time not only by humans but now also by AI, tool in part for inventing tools. We are racing up the vertical, heading clear off the graph.

°°°°°°°°°°°

The Theory of the Adjacent Possible can also be applied to peripheral vision. It takes a critical mass of information, including imagined information, to form a new idea. That insight is the adjacent possible of the thoughts that came before and an adjacent possible to the next round of insights.

From a handful of primordial molecules bouncing around a newly formed planet four billion years ago, through countless adjacent possibles, a door opened to us, to homo sapiens. For that there is only wonder and gratitude.

What doors are we opening? Blessed with peripheral vision, what rooms should we explore next?